The French medievalist, Jean Destrez, in a 1935 essay about manuscript books and copyists of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, provides some interesting comments about the pieces of straw or parchment, stems of flowers and small twigs sometimes found by scholars when consulting or leafing through medieval manuscripts. Then, as now, says Destrez, it appears that readers and writers when interrupted in their study or work utilized the first thing to come to hand to mark a place in a text. He goes on to bemoan the fact that these ad hoc bookmarks are often lost when ancient manuscripts are consulted or rebound. Their loss, he says, is unfortunate because the finding and examination of these items “put there by medieval copyists” could be a valuable source of information adding to our knowledge of the daily life of readers and scribes in the Middle Ages. Thus, tracing the use of ad hoc bookmarks in the Middle Ages calls for some speculation to fill in the gaps where little physical evidence is available or where no written records about their use exists.

In addition to the items mentioned by Destrez, single unattached lengths of vellum, rough cord and string, as well as strips of leather, squares of parchment and pieces of straw have also been found in manuscript books, presumably acting as ad hoc bookmarks. The use of such simple, handy items would have been a quick, practical method of keeping one’s place or marking a page for future reference in early manuscript books, where table of contents, chapter divisions, page numbering and indexing were non-existent.

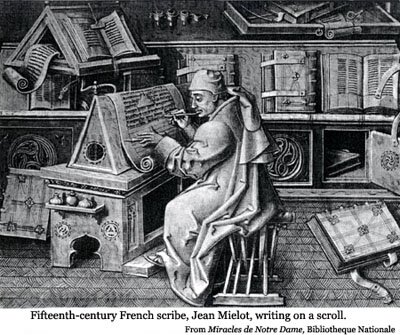

The illustration at the head of this article, taken from Norma Lavarie’s The Art and History of Books (1995) shows a fifteenth-century scribe at work and reveals that many different contemporary items or devices were used as temporary bookmarks in the daily life of the medieval scribe, as he sat surrounded by the books he might need to refer to in his copying work.

The scribe in the illustration is working on a scroll which is laid over an A-shaped writing desk and is held down by a small pyramid-shaped weight attached to the top of the desk by a string or cord. On a small triangular lectern above the desk at which the scribe is working there is a codex manuscript being held open (probably for reference) at a particular page by another oblong weight also suspended down from the top of the smaller lectern by a cord. These weights were a form of “bookmark” used in scriptoria in the Middle Ages to hold pages flat while they were being worked on, or to hold open manuscript books for reading or reference. Doubtless, they were also at times closed within the pages of manuscript books as markers. Scattered around the room in the illustration are a number of other codices (manuscript books). One lying closed on a shelf above the scribe’s head, to the right, has a leather bookmark sticking out from it and lapping down onto the shelf. The way the end of this marker looks to be emerging flexibly from the pages of the codex and falling loosely onto the shelf would seem to indicate that the bookmark is either a piece of leather or vellum rather than anything more rigid, such as a stiff piece of parchment.

A number of the manuscript books in the illustration have two straps attached to their thick board covers. These were often used on medieval codices (especially on the larger manuscript books) to secure them closed when not in use. In two of the books which lie open to the left and right on the shelf next to the seated scribe, the uppermost strap is being used to hold the manuscript open at a certain page—that is the strap is being used as a bookmark. And in another book, lying closed (but not secured with its straps) on the floor behind the scribe, the upper strap is tucked in between the pages of the closed book, again, no doubt, acting as a bookmark keeping a place in the book for future reference. A cabinet behind the scribe has one of its doors held open by the strap of a book on the shelf above it. In the cabinet there can be seen a closed book, lying flat, with a stiff-looking marker of some type sticking out from its top edge, perhaps one of the book’s cover straps or a loose piece of parchment.

The only seemingly purpose-made bookmarks in the picture are a number of register cords, probably strips of vellum or pieces of string, attached to the headband of the volume, which can be faintly seen hanging down or emerging from the lower edge of the open book on the triangular lectern in front of and above the seated scribe. Thus, just this one illustration of a fifteenth-century scriptorium provides us with a peek at a variety of the kinds of items which might have been used as ad hoc bookmarks by medieval readers.

Other illustrations of medieval scribes at work, if examined carefully, would no doubt reveal more of such items being used as bookmarks and add greatly to our knowledge of how a variety of items, not necessarily intended or created for the purpose, but handy to the reader or scribe, were pressed into service as ad hoc bookmarks in the Middle Ages.

For example, Patricia Basing in her study, Trades and Crafts in Medieval Manuscripts (1990), has two illustrations depicting the use of ad hoc bookmarks by scribes in the Middle Ages. The first illustration is from “Memorable Sayings and Acts,” a French translation of a popular collection of anecdotes by the Roman writer Valerius Maximus, and shows a scribe at his desk working on a page of a book held open by the same type of weighted cord mentioned earlier. A second illustration, with the rubric “Scribe Vincent of Beauvais, Lir miron historale, France early 15th century” shows a scribe using a knife to hold open the pages of his book. It would appear that knives and paper cutters of many shapes and sizes have long been used to hold open a book or mark a place in a book, just as they still are today.

Frank’s extensive career in teaching and librarianship began when he taught English in the U.S. From 1961 to 1963, as part of a Columbia University program called “Teachers for East Africa,” he taught English and American Literature in East Africa. There he met his wife, Dorothy. They returned to the U.S. where he simultaneously taught and finished two Masters’ degrees, in Education and in Librarianship. In 1968 they returned to England where Frank taught Library Studies, and adopted Hodge, a cat who later traveled around the world with them. In 1972, Frank was “seconded” for two years to teach at Makerere University in Uganda, East Africa, but left reluctantly after one year when the tyranny of Idi Amin became intolerable. From there it was back to England, then Australia and finally to America in 1979, to Buffalo where Frank earned his doctorate. Later they moved to Colorado, where he was Professor of Library Studies at the University of Northern Colorado until retiring in 1997. Frank published James A. Michener: A Checklist of his Work with a Selected Annotated Bibliography (Greenwood Press) in 1995. He has written on bookmarks, specifically on medieval bookmarks, his special area of interest. A poet by avocation, he writes eclectically but traditionally. Contact Frank.